The “Tucson Artifacts”

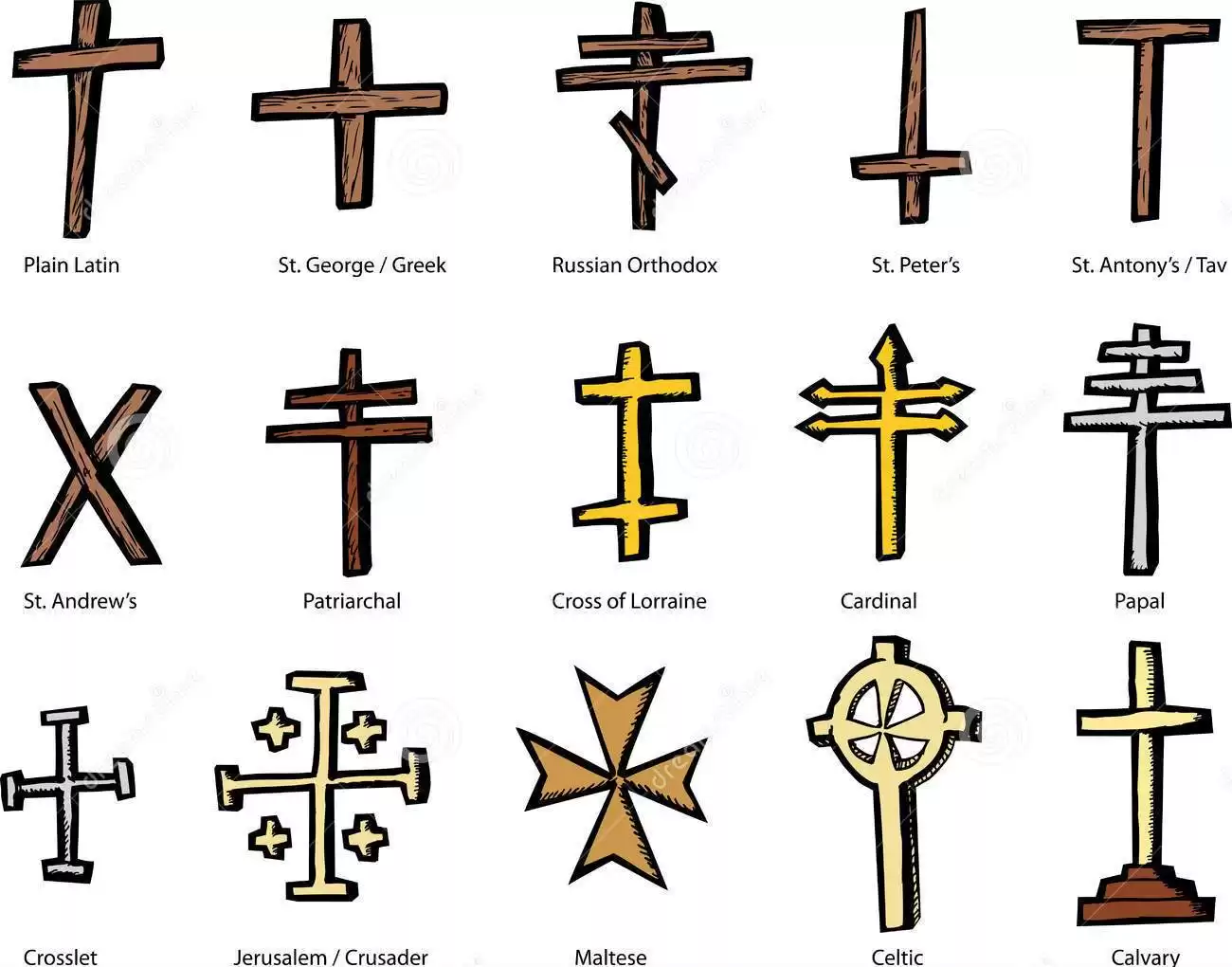

Sit down and hang on because this is a roller coaster of a tale. It begins innocently enough. On September 13th, 1924 Charles E. Manier was out for a Sunday drive with his wife Bessie, daughter Ethel, and father J.E. Manier. As they tooled along Silverbell Road north of Tucson (coincidentally, not far from where we live) they espied an old limekiln in the hillside. Curious, they stopped to investigate. While snooping around Charles noticed a metal object sticking out of the hillside. Charles and his father set upon the caliche (a soil layer of calcium carbonate, similar to concrete, that occurs naturally here) and were rewarded with a lead cross, 18 inches long and weighing 64 pounds.

The Maniers took the cross home, cleaned it up, and found a Latin inscription that was shortly thereafter translated by Frank Fowler, a University of Arizona professor, as “Calalus, the unknown land.” While at the University the cross was handled by multiple professors in several departments.

Speculation about the object’s origin ran wild. Could there have been a Roman presence in southern Arizona? Was this evidence of a lost tribe of Israel? Could this be the great find that finally put sleepy Tucson on the world map? We may laugh at those ideas now, but keep in mind this was the era of astonishing discoveries; the richly fabulous tomb of Tutankhamen was uncovered just two years earlier.

Speculation about the object’s origin ran wild. Could there have been a Roman presence in southern Arizona? Was this evidence of a lost tribe of Israel? Could this be the great find that finally put sleepy Tucson on the world map? We may laugh at those ideas now, but keep in mind this was the era of astonishing discoveries; the richly fabulous tomb of Tutankhamen was uncovered just two years earlier.

Though the academics were clearly fascinated by the cross no one subjected it to a rigorous scientific examination. This lackadaisical handling is part of the reason the origin of the Tucson Artifacts (or Silverbell Artifacts as they are also known) remains a controversy.

Intoxicated by the attention his cross received at the University the giddy Manier showed it to Karl Rupert, an archaeologist at the Arizona State Museum here in Tucson. Rupert too was keenly interested, for he convinced Manier to take him to the discovery location the very next day. While at the site Rupert and Manier unearthed a large caliche plaque covered with Latin inscriptions, which included the date 800 A.D. To say they were excited is an understatement.

A week later the Arizona Daily Star ran an article about the artifacts as evidence of a possible Roman site in southern Arizona. This attracted the attention of experts and historians from across the country who weighed in with strongly worded, diametrically opposed opinions. Some crowed things like, “It’s an authentic discovery of major importance that will rewrite our history books.” While others decried it as a poorly executed hoax by a perpetrator of diminished mental faculties. Bear in mind that many of those pronouncements were made from afar by men who never examined the artifacts or visited the site.

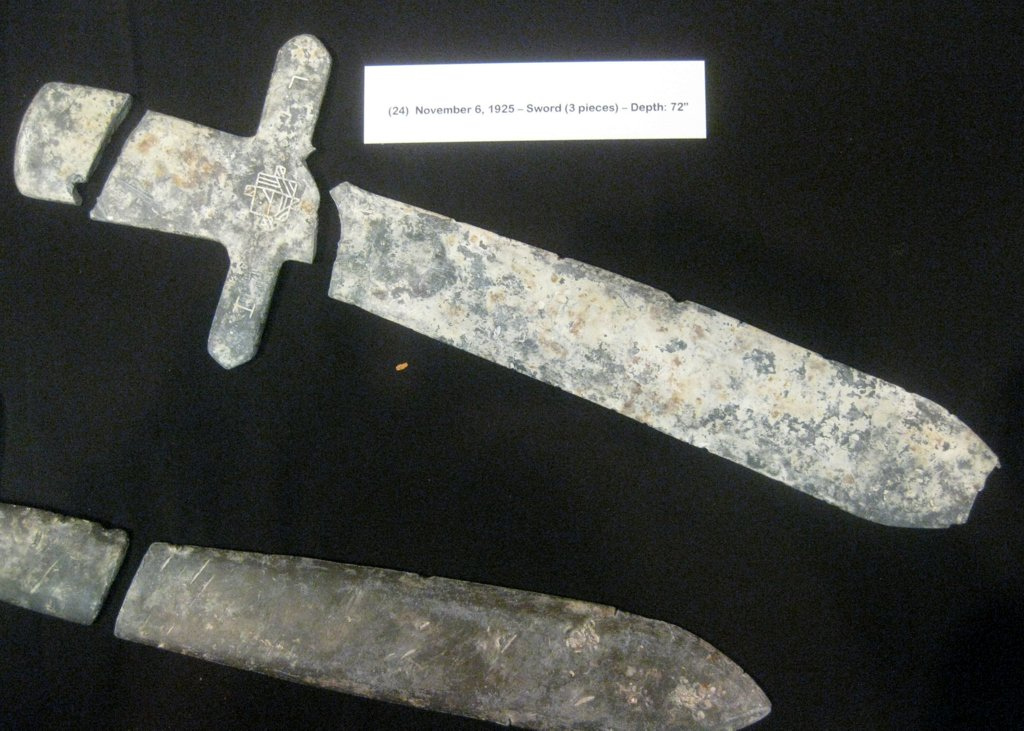

In November Manier and his friend Thomas Bent formed a partnership to continue exploration of the site and promote the find. By February 1925 Bent had moved into a shack near the site in an effort to homestead the unowned land. He and Manier were certain the discovery would soon prove profitable. As they dug deeper the site continued to yield items: several more lead crosses and a couple of lead swords, all of them covered with inscriptions. During the excavation Bent took detailed notes about the work, the artifacts, and the folks involved.

In November Manier and his friend Thomas Bent formed a partnership to continue exploration of the site and promote the find. By February 1925 Bent had moved into a shack near the site in an effort to homestead the unowned land. He and Manier were certain the discovery would soon prove profitable. As they dug deeper the site continued to yield items: several more lead crosses and a couple of lead swords, all of them covered with inscriptions. During the excavation Bent took detailed notes about the work, the artifacts, and the folks involved.

Manier and Bent enlisted the help of Lara Coleman Ostrander, a local art teacher who had also studied history. It was her job to sketch each item, transcribe the inscriptions, and translate the phrases. She is the person credited with stitching together the story of Calalus, a Roman settlement, from the various items. In 1925 Ostrander and geologist Clifton J. Sarle co-wrote an assessment of the Manier and Bent site. They were convinced that the Tucson Artifacts were evidence of a Judeo-Christian settlement. The story made headlines in the New York Times.

Then the wheels started to come off their grandiose claim. Professor Frank Fowler (yep, the very man who translated the first cross for Manier) said in a 1926 Arizona Daily Star article that the inscriptions were taken straight out of Latin grammar books. After visiting the site and examining several artifacts, Emil Haury (who was studying at the UA on his way to becoming a world-renowned archaeologist) proclaimed it to be a hoax. Another geologist, James Quinlan, retired from the U.S. Geological Survey, countered Sarle’s claims of ancient emplacement by proving that caliche could easily be man-made and placed around new objects. Even Manier’s partner, Thomas Bent, did damage when he shared information given to him by a local; that Timoteo Odohui, who lived nearby, was a sculptor with a love of languages who was known to work with lead.

The doubts mounted until most early believers recanted. Manier continued to dig up artifacts for several years—the last one was removed in 1930—but there was no longer any interest. Despite the ridicule heaped upon Manier, his family, and close associates, they remained convinced of the authenticity of the site and the 32 artifacts. As time went on the story of the Tucson Artifacts faded from the spotlight.

The doubts mounted until most early believers recanted. Manier continued to dig up artifacts for several years—the last one was removed in 1930—but there was no longer any interest. Despite the ridicule heaped upon Manier, his family, and close associates, they remained convinced of the authenticity of the site and the 32 artifacts. As time went on the story of the Tucson Artifacts faded from the spotlight.

As a teenager I stumbled across the tale in a book of Arizona oddities and I thought it sounded pretty far-fetched. Romans in Tucson? Yeah, right. Or in the parlance of the day, as if. So imagine my surprise when I heard that the Tucson Artifacts are once again back in the media.

“The Desert Cross” is the name of a recent episode of a new series called America Unearthed (which airs on the H2 network, a History Channel product) that re-examined the Tucson Artifacts. For the filming, the crew came to Tucson to examine the artifacts in the Arizona History Museum archive, visit the dig site, and spend time with Mr. Bent’s grandson. I recently watched the program in which Scott Wolter, the show’s host, concluded that the geology couldn’t have been faked.

In other words, he doesn’t believe the Tucson Artifacts were part of an elaborate hoax. He says the evidence proves they are real. So here we go again. Roughly 90 years later mystery still swirls around the Tucson Artifacts. Want to see for yourself? The artifacts are on display at the Arizona History Museum in Tucson for the next month or so. The museum also houses archived documents relating to the discovery if you’re really interested.

Photos: View our Tucson Artifacts photographs.

Video: Watch the full episode of “The Desert Cross” (on America Unearthed) on YouTube.