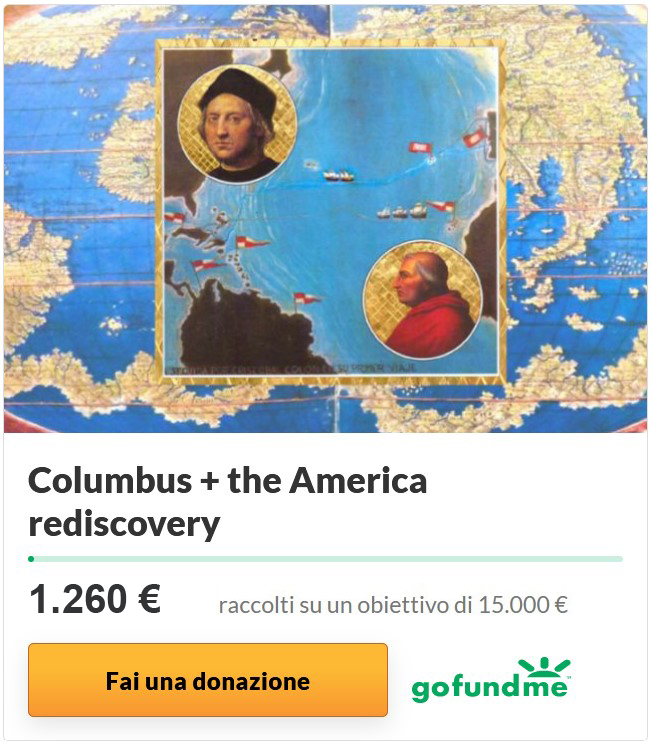

From Ancient Egyptians to extra-terrestrials, popular literature has identified various peoples and personages with the discovery of the Americas. Absent from this familiar list was the Pope, that is until very recent historical times. Italian journalist and author Ruggero Marino claims that Pope Innocent VIII sponsored Christopher Columbus' first voyage. And, in the fashion of the later-published "Da Vinci Code", he has written "Cristoforo Colombo ed Il Papa Tradito" (available only in Italian) stating his case.

Using a blend of conjectures, coincidences, curiosities, and certainties, the author paints a picture of a Watergate-style cover-up surrounding Columbus' initial voyage. The tale involves many great figures of the Renaissance. This cover-up erased the role of Pope Innocent VIII in the discovery of the New World. To be sure, there is independent evidence which credits the Pope. For example, on his tomb there is an inscription that refers to his having a part in the discovery of the new lands. Furthermore, respected Scottish historian William Robertson, an 18th century colleague of philosopher David Hume, notes the Papal role in his rare book on the discovery of America.

But, just what was this Papal role? According to Marino, the Pope, not Queen Isabella- or her hocked jewels- provided the funding for Columbus' expedition. In his long quest to obtain funding for his voyage of discovery, Columbus, a Genoese, would have appealed to the powerful banking establishment in the still-great Italian maritime power of Genoa.

Marino alleges a more particular motive and connection: Columbus may have been the illegitimate son of Pope Innocent VIII, himself a familiar figure in Genoese life. This conclusion is based on the contents and tone of several of Columbus' letters.

Certainly, the Pope was related to the great Medici family, the first family of Florence and patron of artists including Michelangelo. Between the Genoese and Florentine connections, the Pope had ample ability to provide funding. It is also noteworthy that Genoese bankers were very active at the Court of Isabella. A member of the well-connected Geraldini house was the Papal Nuncio at the Court. Another Papal ally had control over the special collections of the Spanish faithful. But why would the Pope direct funding to a speculative venture, even if his illegitimate son were its sponsor?

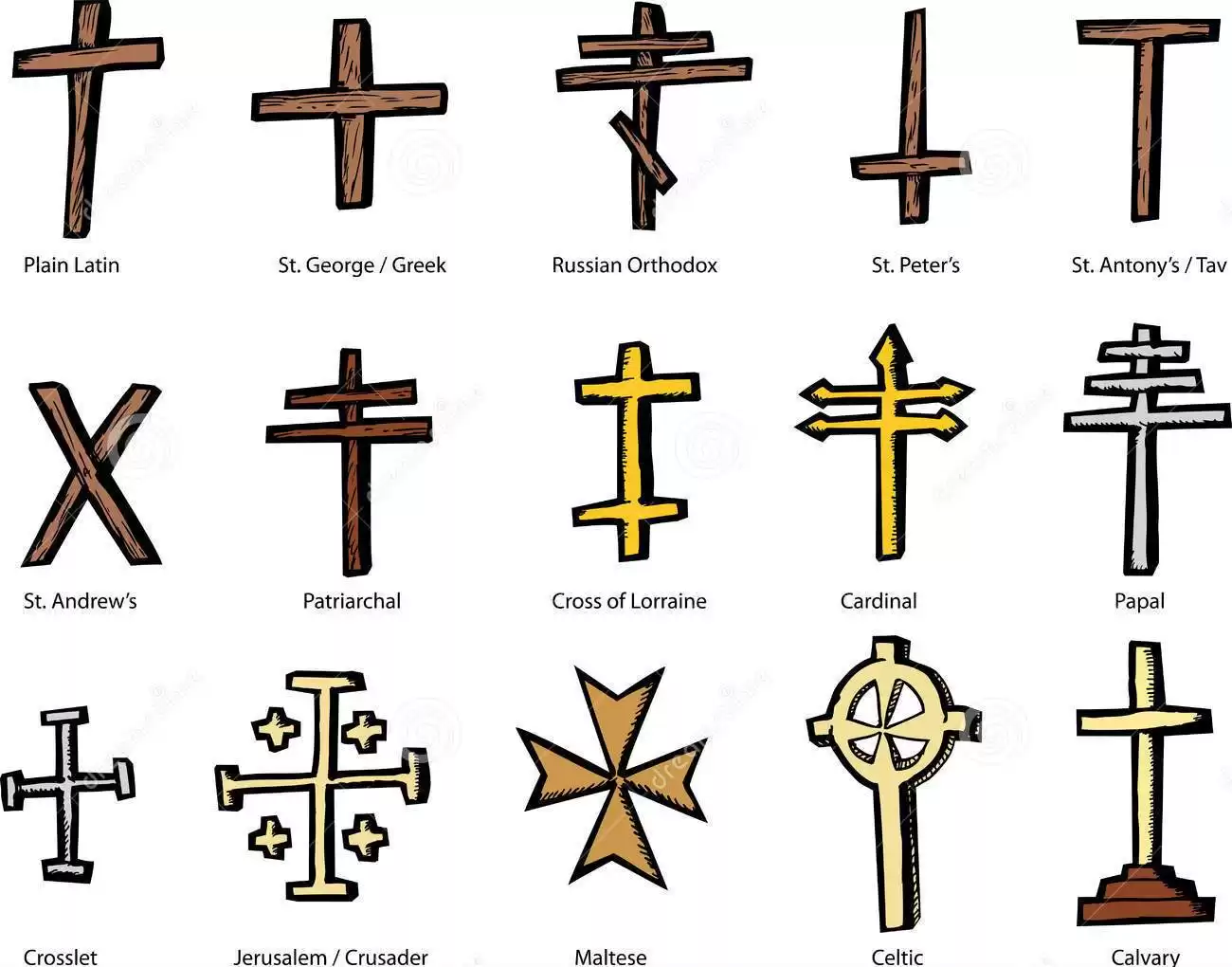

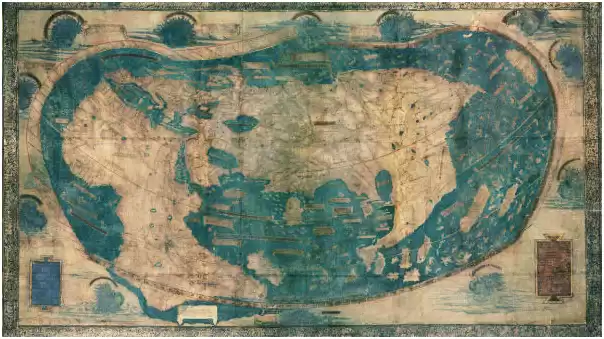

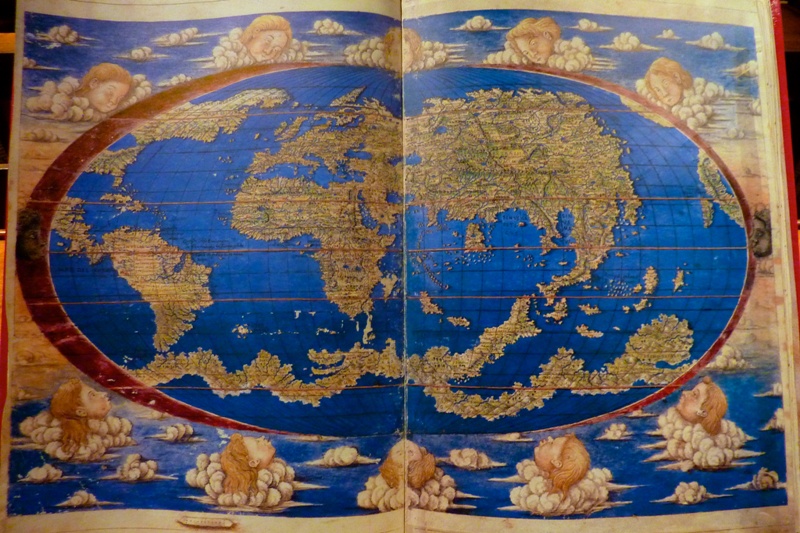

The answer to this question is the crux of the matter, the pivot point on which the alleged cover-up turns. In 1492, the world was in the midst of a great geo-political revolution which only hindsight could reveal with clarity. Barely forty years before Columbus left Spain, the Eastern Roman Empire finally disappeared. The great Sultan Mehmet II had conquered Constantinople in 1453. Still many in the west were not willing to let go of the Roman ideal, among them Pope Innocent VIII. It was the Pope's hope to sponsor a grand crusade to defeat the Turks and capture Jerusalem.

Again, according to Marino, the finances for such a huge adventure were to come from the discoveries of Columbus!

Seven days before Columbus set sail, Pope Innocent VIII died. Columbus set sail into a future that changed the world, but his world was also changing behind him. The new Pope was Alexander VI Borgia, a Spaniard. Alexander's illegitimate son, Cesar Borgia is "The Prince" on whom the Florentine Machiavelli models his famous work about politics. Cesar sought to expand Papal lands in Italy.

The world of Columbus became entirely dominated by Spanish interests. So much so, that the Borgia Pope decided to split the world between Spain and Portugal in his famous Bull, Inter Caetera, issued in 1493. Cristoforo Colombo was better off now as Cristobal Colon.

It is possible, as Marino suggests, that the Italianate Pope Innocent VIII's sponsorship of the expedition was covered up, banished to the secret archives in the Vatican, for the greater glory of Spain.

So what is the truth? Apart from the difficulty of establishing historical claims, we are confronted with the dilemma and the difference between the methods of journalism and history. The two fields use different approaches to arrive at truth. Like Einstein, journalists are prone to believe there are no coincidences. Historians take an intricate, complex path before attempting conclusions.

Perhaps the final evidence awaits discovery in the secret archives of the Vatican. But perhaps not.

Article published in Chicago, Newark and Salt Lake City